|

| Village Collection: On Li Mu’s Qiuzhuang Project | Date :2014-05-26 | From :iamlimu.org |

| ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ |

![]()

Jesse Birch

In August 2012 the artists’ collective Zuzhi (Zhao Junyuan, Tao Yi, Xu Zhe, and Li Mu)

presented the exhibition WOOD WORK at Shanghai’s V Artspace. Each artist engaged

with wood as both a medium and a theme, looking at the physical and cultural

properties of the material from different points of view. While most of the works in

the exhibition were actually made of wood, Li Mu’s contribution was a spoken

narrative sound piece called My Father (2012), played from simple speakers mounted

to the ceiling of the space.

Li Mu comes from a small Chinese woodworking village of about one thousand

people in Jiangsu province, called Qiuzhuang, where his father worked as a

carpenter. Through this sound work, Li Mu tells of the disconnect he felt between

himself, his father, and the village as a whole while he was growing up and becoming

an artist. The material of wood weaves in and out of

the story as the narrative unfolds.1 This work marks the beginning of Li Mu’s artistic

engagement with his home village.

Li Mu, My Father, 2012, sound installation in the exhibition Shanghai. Courtesy of

Li Mu.

Li Mu, Shanzhai Van Abbemuseum, 2013, installation view in the Artspace, Shanghai.

Courtesy of Li Mu.

A year after the WOOD WORK exhibition, I visited V Artspace to see a different group

exhibition, THE SUN, during the worst heat wave eastern China had seen in 140

years. THE SUN featured at least twenty-five artists, including three of the members

of Zuzhi. Upon entering the exhibition space, I was dwarfed by a photographic wall

mural by Li Mu titled Shanzai Van Abbemuseum, which depicted a dry dirt road

running through a rural village in China. In the picture, two small industrial vehicles

pass stacks of logs, piles of rubble, and a brick wall adorned with three painted

images of Mao Zedong.

Seeing the Chairman’s likeness on the walls of a village wasn’t surprising in itself, but

these weren’t official Party images; they were versions of Andy Warhol’s colourful

Mao, from 1972. Warhol’s massive retrospective, 15 Minutes Eternal, had recently

closed in Shanghai and was about to open in Beijing, but state censorship had

prevented Warhol’s Maos from being included in either show.

The images of Mao depicted in Shanzai Van Abbemuseum, however, are part of Li

Mu’s Qiuzhuang Project: A Dispersed Museum (December 2012– ongoing), a long-

term engagement with the artist’s home village. In this project, significant works

from the collection of the Van Abbemuseum in Eindhoven, the Netherlands, are

reproduced and installed in Qiuzhuang. This photomural of a scene from the

Qiuzhuang Project, along with a descriptive text about the project sourced from an

American blog,2 was Li Mu’s contribution to THE SUN.

The title of this mural suggests a questioning of authenticity. Shanzai means

knockoff or imitation, but this hardly does justice to the layers of reproduction and

reception happening in Li Mu’s Qiuzhuang Project. With the inclusion of the blog

text, this work indexes multiple potential ways of experiencing the project and its

three particular types of audience: the art community in Shanghai where Li Mu had

been living and working until recently, the globally dispersed online audience, and

the audience that Li Mu values most—the Qiuzhuang villagers themselves.

Two days later, and after three hours on the high-speed Harmony train plus an hour

in a taxicab operated by an old friend of Li Mu’s, I was standing in the village of

Qiuzhuang. It was even hotter there than in Shanghai, and I began to wonder if this

was why Li Mu included an image of this place in THE SUN. The dirt road in the

photomural is actually the village’s main road and, along with the Warhols, it now

serves as a museum for numerous reproductions of works from the Van

Abbemuseum’s collection. On display are pieces by Daniel Buren, Dan Flavin, John

Kormeling, and Sol LeWitt, with videos of performances by Marina Abramovic and

Ulay on a permanent loop in the village’s rudimentary grocery store. At the time of

writing, there are still plans in the works for Carl Andre and Richard Long pieces to

be fabricated.

The artworks Li Mu chose to exhibit in Qiuzhuang are directly linked to a particular

lineage in the trajectory of Western modern art, but contrary to the modernist notion

of artistic autonomy, the Qiuzhuang Project

Qiuzhuang Project, 2012– ongoing, with Andy Warhol's Mao paintings, 1972.

Courtesy of Li Mu.

Qiuzhuang Project, 2012– ongoing, with Daniel Buren’s Courtesy of Li Mu.

has its own particular engagement with external indexes and influences, complicated

by problems of reproduction, reception, and translation. Each “original” artwork, as it

made its way from its place and time of creation to its home in the permanent

collection of the Van Abbemuseum was already transformed through numerous

contextual shifts and through the passage of time, but what, if anything, is left of the

work now that it has become part of the Qiuzhuang Project? Do the stripy Daniel

Buren pieces that once followed the artist’s desires to take them out of the institution

and onto the streets still speak the same language when they find their way, via a

museum’s collection, through reproduction, to the front of a provisional garden of

corn on a dirt road in a small Chinese village?

Walter Benjamin speaks of the changes that occur once an artwork is completed, in

terms of “subject matter” and “truth content.” For Benjamin, when a great work is

first made, the subject matter and the truth content are fully intertwined, but

through the contingencies of context, and the passage of time, the two diverge, and

the truth content becomes less and less perceptible. If one subscribes to the

existence of a transcendental essence of truth (the most modernist of notions), can

that essence be supplanted with a new one? In his essay The Work of Art in the Age

of Mechanical Production, Benjamin famously argues that through reproduction, the

original artwork loses its essence, its aura. Boris Groys points out, however, that

Benjamin, for all of his foresight, was mistaken when he wrote from a position that

assumed a particular normative origin for each work. As Groys states:

There are no eternal copies, as there are no eternal originals. Reproduction is as

much infected by originality as originality is infected by reproduction. In circulating

through various contexts, a copy becomes a series of different originals. Every

change of context, every change of medium, can be interpreted as a negation of the

status of a copy as a copy—as an essential rupture, as a new start that opens a new

future. In this sense, a copy is never really a copy but rather a new original, in a new

context.3

In China, the production of “new originals” is a massive industry, and when

considering the act of reproducing famous Western artworks, another village comes

to mind: Danfen Village, where thousands of artists work producing countless

imitations of renowned paintings and prints for domestic and international sale

(including Andy Warhol’s Mao.)4 But Qiuzhuang is not Danfen, and while it would

have been faster, cheaper, and easier to have much of the work made elsewhere in

China, Li Mu made a clear decision to work directly with his community to create a

decidedly local museum of reimagined Western Art. With presentations like Shanzai

Van Abbemuseum, and on his Web site, Li Mu facilitates the reception of the project

outside of Qiuzhuang, but the villagers are his primary audience.

In China, often known in the West as the global hub of cheap, alienated labour, Li Mu

decided to produce these artworks in the most un-alienated way possible. He worked

with the expertise of those around him to create the works and to respond to the

contingencies of the local while fostering a kind of shared understanding. Rather

than being revealed to the public once they were complete, a good portion of Li Mu’s

local audience took part in the production of the work itself. Through the process of

making and displaying these “new originals,” stories and relationships evolved.

While the Qiuzhuang Project is seen by some as an importation of Western values to a

rural Chinese village through art, what Li Mu is doing is more subversive. Like most

contemporary artists, Li Mu is using pre-existing ideas and aesthetics and radically

transforming them by setting them in sharp relief against the conditions of reality. Li

Mu is not indoctrinating the villagers into Western culture; he is allowing the village

to be impressed onto the artworks. The villagers, while interested in what Li Mu is

doing, come to these things in their lives on their own terms, and some don’t come

to them at all.

The first art object from the Van Abbemuseum collection that was produced in the

village was a zigzag, ladder-like sculpture called Untitled (Wall Structure) first made

by Sol LeWitt in 1972. Li Mu didn’t just produce the artwork as it was when LeWitt

first created it, he made it informed by Superflex’s Free Sol LeWitt project, in which

the Danish collective fabricated versions of this artwork in the Van Abbemuseum and

gave them to visitors free of charge. These works not only moved into unlikely

contexts and acquired new narratives of their own, they infected the “original” work

with the further potentiality of freedom.

Li Mu “borrowed” the Untitled (Wall Structure) already coloured by the Superflex

intervention and worked with a small group of villagers to reproduce fifteen of them.

They were then distributed to interested people in Qiuzhuang. Through the process

of creating these sculptures, Li Mu began making new connections in his village and,

producing these

Qiuzhuang Project, 2012– ongoing, with Sol LeWitt's Untitled (Wall Structure), 1972.

Courtesy of Li Mu.

Qiuzhuang Project, 2012– ongoing, with Sol LeWitt's Wall Drawing No. 480,

1986.

Qiuzhuang Project, 2012–ongoing, with Sol LeWitt's Wall Drawing No. 256, 1975.

Courtesy of Li Mu.

ostensibly useless art objects, created something useful: community ties. However,

once these works started appearing in people’s houses they acquired other kinds of

usefulness. Li Mu’s father installed the sculpture on the ceiling of his garage so it

could be used to hang his bird cages; his neighbour installed his on an angle and

used it to display his travel souvenirs and trinkets. Soon the wall sculptures became

coveted. Having missed out on the original distribution, one young man made his

own wooden version as a shelf in his living room. The first Untitled (Wall Structure),

safe within the confines of the Van Abbemuseum’s collection, is now informed by the

fact that it has siblings doing peculiar things, not only around Eindhoven, but also in

Qiuzhuang, China.

In addition to the distributed sculptures, Li Mu collaborated with a number of

assistants to paint two other Sol LeWitt works: Wall Drawing No. 480 and Wall

Drawing No. 256, on the outsides of buildings. Among Li Mu’s assistants was Lu

Daode, a village elder and calligraphic painter. Li Mu became aware of this skilled

painter when he was younger and wanted to become a painter himself, but had no

particular reason to connect with him. When planning the Sol LeWitt wall murals, Li

Mu attempted to hire Lu Daode to help paint. At first he was uninterested in

participating, but Li Mu was persistent, and Lu Daode eventually agreed.

The village has no written history, so in order for stories of the past to be retained,

they have to be told over and over again. The sharing of labour is also conducive to

sharing stories. As Benjamin observes “The more self- forgetful the listener is, the

more deeply is what he listens to impressed upon his memory. When the rhythm of

work has seized him, he listens to the tales in such a way that the gift of retelling

them comes to him all by itself.”5 Lu Daode, who worked with his hands all of his

life, was clearly a practiced storyteller. I heard stories from Lu Daode through Li Mu

even before I met the painter. These stories as they circulate through word of mouth,

Li Mu’s blog, and now this essay, become an important part of the Qiuzhuang

Project.

The village has in many ways determined Lu Daode’s life and career. Early in his life,

he was a painter specializing in flowers and birds, and as we sat under his shrine to

Mao, eating grapes from his vine and listening to his songbirds, he told us that

during the Cultural Revolution he was invited to a group exhibition, but the state

decided that his paintings of natural things did not serve the advancement of

Communism, and so he was forbidden to participate. Shortly thereafter, a theatre

troupe asked him to join them as a set painter, but because of the hukou residency

permit system, which determines where one can work, live, receive education, and

raise a family, he was unable to leave the village. He eventually gave up painting for a

living and, like many others in the village, became a woodworker and general

handyman.

Since retiring he has begun painting full time again, specializing in Chinese folk

goddesses. He has once again become renowned, and his new paintings are coveted

by spiritual mediums who use them to facilitate communication with the gods. When

I asked him what he thought of the Sol LeWitt wall drawings, one mustard-coloured

with rainbow pyramids and the other a network of intersecting white lines, he said

that while he enjoyed Li Mu’s company, he does not like painting things that are not

useful.

For Lu Daode, useful meant pictorial, but, as suggested earlier, many of the works in

the Qiuzhuang Project have become useful in different ways by virtue of necessity. It

is said that when useful things enter a museum they become art, but the reverse is

also true; when artworks are far enough from the museum, they can become useful

again. Like the Sol LeWitt wall sculptures that have become shelves and hangers, the

Dan Flavin and John Körmeling light works have become streetlights. In the evenings

villagers linger nearby as these artworks provide the first nighttime illumination the

dirt road had ever seen.

John Kormeling's HI HA (1992), which consists of the words HI HA repeated

numerous times in red and yellow carnival lights, was installed directly across the

street from the small general store. Thanks to the illuminated artwork, the shop has

become a popular hang out at night. The store is owned by Li Mu’s uncle, Wang

Guoqi, and on a single monitor perched atop a refrigerator next to the store shelves,

the complete collection

Qiuzhuang Project, 2012–ongoing, with Sol LeWitt's Untitled (Wall Structure), 1972.

Courtesy of Li Mu.

Qiuzhuang Project, 2012 ongoing, with Marina Abramovic and Ulay's video

compilation in a Qiuzhuang grocery store. Courtesy of Li Mu.

Qiuzhuang Project, 2012–ongoing, with John HI HA, 1992. Courtesy of Li Mu.

of Marina Abramovic and Ulay's performance documentation, up to their farewell on

the Great Wall of China, plays on a loop. Li Mu’s uncle is a very outgoing guy, and the

grocery store is a social place, so the video weaves its way into

everyday conversations: sometimes out of interest and sometimes out of discomfort.

Other than the Warhol portraits of Mao, which are deemed by some to be

disrespectful, the only artwork in the Qiuzhuang Project that villagers really feel

uncomfortable with is the famous Abramovic and Ulay work, Imponderabilia (1977),

in which the naked artists face each other in the entranceway to the museum forcing

visitors who wish to enter to choose between facing one of them or the other as they

squeeze through. Li Mu’s uncle acts as a spokesperson for the video explaining that

it’s not meant to be sexual, but rather to show the natural form of the human body.

While this might be itself a contestable position, it seems to have satisfied the local

naysayers. Currently Li Mu’s uncle is reading an Abramović autobiography so

that he can be a more informative host.

These encounters with the contingencies of everyday life are what Li Mu feels are the

most important elements of his project. In a letter to Charles Esche, director of the

Van Abbemuseum, Li Mu explains his thoughts around the encounters between the

village and the artworks using the context of John Körmeling's, HI HA as an example:

The owner of the house planted beans in front of the installation. Soon the beans

crawled over the whole rack and covered most of the installation. When the art is

confronted with people’s practical interests, it gives way to the latter. Therefore they

can coexist in

a harmonious way and enrich the artworks. Because what I care about is the

relationship between the art and its surrounding environment, not the art itself.The

Van Abbemuseum has a sophisticated approach to sharing its collection. Other recent

projects, like Picasso in Palestine and the aforementioned Free Sol LeWitt, also

involved unconventional modes of distributing works from the institution’s collection.

Picasso in Palestine was initiated by Khaled Hourani, artist and artistic director of the

International Art Academy Palestine, and realized through collaboration between the

Academy and the Van Abbemuseum. The complications that arose from attempting

to ship and display a priceless artwork in occupied Palestine, became part of the

work, and will be imbedded in the cultural understanding of the painting from now

on. The painting, Buste de Femme (1943), depicts a woman with an almost

mechanical cubist visage, what Slavoj Žižek calls an “occupied face,”

showing that even a Picasso is not free from the influences of contextual shifts.7

Buste de Femme will return to the Van Abbemuseum as an occupied face. What

projects like Free Sol LeWitt, Picasso in Palestine, and Qiuzhuang Project show is that

when artworks enter new territories, they forever carry those territories with them.

Qiuzhuang Project is supported by the Van Abbemuseum, but, how and if the work

will enter the museum (again) is still unclear, and perhaps the lives of these works are

only beginning.

In considering this project and its institutional connection, it is important to

remember that Li Mu is not working as some kind of adjunct curator for the Van

Abbemuseum; he is working as an artist, and while the project still seems malleable,

this is the norm for Li Mu, an artist whose work is process- based, socially-oriented,

contingent, and difficult to pin down. For example, in 2009 he found a stranger’s

name card in Shanghai, and for one year he sent this person a present every month

without ever indentifying himself. For Double Infinity, an exhibition produced

through a partnership between the Van Abbemuseum and Art Hub Asia and held at

the Dutch Culture Centre in Shanghai parallel to the World Expo 2010, Li Mu

simultaneously acquired cultural and monetary capital. For his contribution, the artist

simply requested a job working for Van Abbemuseum as a general employee, being

paid at the European standard (New Job, 2010). This tension between social and

cultural expectations to make a tangible income, and the artists desire for creative

sovereignty, is present in Qiuzhuang Project as well.

Li Mu, Blued Books, 2008–09, juvenile prison library project. Courtesy of Li Mu.

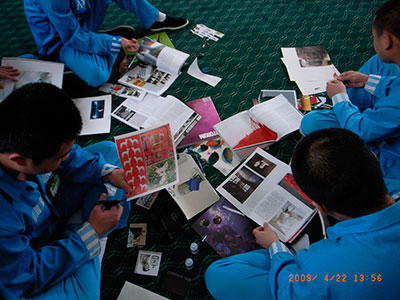

Qiuzhuang Project, 2012– ongoing, Children reading in

Recently Li Mu has instigated a number of projects involving books and libraries. For

Public Knowledge (2008), he opened his personal library to the public, allowing

visitors to borrow books on the honour system. Later, for Blued Books (2008–09), he

worked with inmates at a juvenile prison facility to develop a library for them, and

offered mentorship if they needed it. As curator Biljana Ciric says of this work, this

approach ␣moves beyond the productive role of the artist, affording him the more

complex role as a friend or teacher, as someone who listens and is situated between

the institutional system and its subjects.8 It is in this unanchored interstitial zone

that Li Mu’s art happens.

The Qiuzhuang Project began with a library too. Before Li Mu started producing the

artworks, he opened a library, known as “A LIBRARY,” where adults and, especially,

children could find information about the artworks if they wanted. Perhaps more

importantly, library patrons could just spend time reading or watching a movie. Li Mu

sees the library as a space to help reconnect him to his community, by providing

something that he dreamt of but never had as a child: a place for exploring culture.

As he explains “The library is a public space that connects local people with the

outside world and helps [in] establishing a reciprocal understanding. Through the

library, I can spread my knowledge and experience gradually, let the villagers

understand me, and acknowledge the next steps of the project.”9 This slow process

of development is central to the Qiuzhuang Project’s local success, but its reception

elsewhere functions much differently.

Qiuzhuang Project, 2012–ongoing, with Dan Flavin's Untitled to a man, (George

McGovern), 1972. Courtesy of Li Mu.

I first came to know about the project on the Van Abbemuseum’s Facebook page, but

while I could have written this essay having never visited the village, and I didn’t

know what more I expected to understand by visiting Qiuzhuang, I decided that if I

didn’t go, the possibility of an impoverished understanding was too great. When

speaking with villagers, however, I was confronted by the fact that understanding is

dispersed there too. Qiuzhuang is rich in specificity, but at the same time it is prone

to the contingencies that come with global networks of capital and communication.

These contingencies will also impact the village in a tangible way: soon the dirt road

will be widened and paved to connect two main roads, and most of the houses and

workshops that are supporting the artworks in the Qiuzhuang Project will be

expropriated and destroyed to make room for it. It’s unclear what kind of legacy the

Qiuzhuang Project will have in the village, but

while Li Mu is more concerned with the process than with the end result, for the

duration of my time in Qiuzhuang, his assistant, Zhong Ming was documenting every

conversation. Li Mu hopes that by the end of a year he will have a documentary that

not only records the project, but also the passing of time.

Now that the Qiuzhuang Project has been in process for almost a year, at least one

thing is certain, Li Mu’s connections with his father and the village have improved. As

Li Mu relates in the sound work that I mentioned at the beginning of this essay (My

Father, 2012), one day his father asked him “Like me seeing the birds that I raise, do

you feel great when you see your works?” Li Mu answered, “Yes, the birds are your

works.”10 Recently Li Mu uploaded two pictures onto his Web site under a post called

Untitled. One was of his neighbour, who was one of the main builders of the Dan

Flavin work, proudly holding up what looks like massive orchid, and the other image

was of the artist’s father holding a cage with his prized canaries.11

Notes

1 Li Mu, “Carpentry,” I Am Li Mu, http://www.iamlimu.org/blogview.asp?

logID=186/. 2 Greg Allen, “Shanzai Van Abbemuseum by Li Mu,” 2013, Greg.org,

2012, http://greg.org/

archive/2013/06/07/shanzhai_van_abbemuseum_by_li_mu.html/.

3 Boris Groys, “Politics of Installation,” e-flux journal no. 2 (January 2009),

http://www.e-flux.com/ issues/2-january-2009/.

4 John Seed, “The Ghosts of Chairman Mao and Andy Warhol Haunt a Hong Kong

Auction,” Huffington Post, May 27, 2010, http://www.huffingtonpost.com/john-

seed/the-ghosts-of-chairman-ma_b_590907. html/.

5 Walter Benjamin, “The Storyteller: Reflections on the Works of Nikolai Leskov,”

in Walter Benjamin: Selected Writings Volume 3, 1935–1938 (Cambridge: The

Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2002), 143.

6 Emphasis mine. Li Mu, “Letter to Charles 6,” I Am Li Mu, May 27, 2013,

http://www.iamlimu.org/ blogview.asp?logID=272/.

7 Slavoj Žižek, “Slavoj Žižek in Conversation About Picasso in Palestine,” Van

Abbemuseum/Youtube, June 23, 2011, http://www.youtube.com/watch?

v=Z3lvYqOVlv4/.

8 Biljana Ciric, “Back to the Basics: Li Mu’s Perception of Human Relations and

Social Interactions,” I Am Li Mu, September 5, 2011,

http://www.iamlimu.org/blogview.asp? logID=122/.

9 Li Mu, “About Qiuzhuang Project,” I Am Li Mu, March 11, 2013,

http://www.iamlimu.org/ blogview. asp?logID=214/.

10 Li Mu, “Carpentry,” I Am Li Mu, 2012, http://www.iamlimu.org/blogview.asp?

logID=186/.

11 Special thanks to Gu Ling for acting as translator on my trip to

Qiuzhuang.

|

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

© iamlimu.org 2011 |

|